New Study: Galveston Bay’s Lead Levels Are Low, 25% Human-Sourced

Researchers recently found that despite low lead levels in Galveston Bay, approximately 25 percent is estimated to be anthropogenic.

Jun 4, 2021

Approximately 25 percent of the lead in Galveston Bay is from human sources, a new study says. This study used state-of-the-art geochemical modeling for environmental analysis. Scientists from the University of Houston, New Mexico State University, Texas A&M University, and Texas A&M University at Galveston used a novel method of lead isotope measurement to “fingerprint” lead sources to Galveston Bay.

Despite the high proportion of lead from human influence, the study finds overall lead concentrations to be below benthic (bottom-dwelling) ecology toxicity thresholds set by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“Galveston Bay is such a rich system to study because it’s a natural estuary that also has strong anthropogenic influences because of industrialization along its shorelines,” Dr. Jessica Fitzsimmons, co-author and associate professor in Texas A&M’s Department of Oceanography, says. “So, it is a perfect place to study contaminant cycling within natural systems.”

While there are no known lead ore deposits in Galveston Bay, there are other sources of naturally weathered lead that enter the system through river water. Despite this, the scientists found that bay sediment leaches (weak chemical dissolutions which access the surface-most portions of the sediments) were approximately 84% anthropogenic, while the overall bulk sediments were mostly derived from natural lead sources.

This research emphasizes that sediment leaches access the same surface-most pools of lead that biota might access within Galveston Bay sediments, and these lead pools are dominantly human-supplied.

Dr. Peter Santschi, a Regents Professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston, praises the paper as “a nice demonstration of an application of stable isotopes that can delineate sources.”

“It’s a powerful method, and they are very good at it,” says Santschi, who was not part of the research team.

He explains that the Houston ship channel (HSC), which is constantly dredged for large ship passage, acts as a sediment trap. The constant dredging creates dredge islands to the sides of the HSC.

“It is difficult to sample in the HSC because it is dangerous with the high traffic of large ships and tankers,” Santschi says. “The only way is to look at or near the dredge islands.”

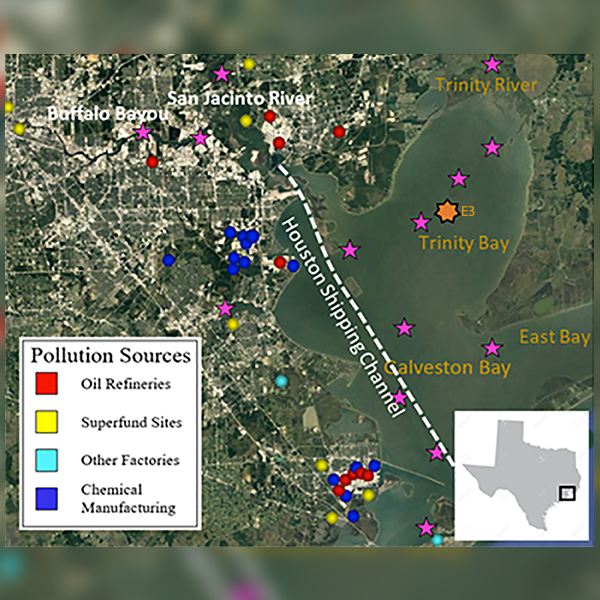

Samples for this study were collected from tributaries that drain into Galveston Bay, the San Jacinto and Trinity Rivers and Buffalo Bayou, and across the entirety of Galveston Bay at various “bay stations”. Collection took place quarterly between June 2017 and June 2019 and the researchers also used a previously collected (July 2016) sediment core. The core sample (E3) was used to compare current lead levels to what was found in the core sample dating back 150 years.

As the scientists expected, lead levels steadily rose over the last 150 years, which coincides with human industrial growth in the area. However, those levels began to level off in the 1990s, possible due to policy changes such as the elimination of leaded fuels in the U.S.

“We were hoping that lead concentrations in the last couple decades would have gone back down, but we did not see as much of the downturn as we might have hoped, given the recent clean-up efforts in Galveston Bay,” Fitzsimmons says.

The study also provided some unexpected results in certain areas. For example. lead concentrations were surprisingly higher in eastern bay areas, which are mostly surrounded by natural refuge lands, than in the western bay areas closer to Houston and its industrial ports.

The scientists believe that complex chemical interactions occur when freshwaters from the Trinity River, which empties into the east side of the bay and is the highest freshwater contributor to the bay, meets the seawater entering the bay from the Gulf of Mexico. These complex chemical interactions cause natural, riverine lead that is dissolved in Trinity Bay waters to attach the surfaces of sediment grains, causing the higher concentrations in the east.

“Circulation of sediments and residence times may be a more important part of the story than we previously considered,” Fitzsimmons says. “The Trinity River source supplies so much freshwater that it drives the salinity gradient across the entire bay, which forces the lead out of the water and onto the sediment grains.”

Lead concentrations in Oyster Bayou on the southeast side of the bay were also higher than expected. Fitzsimmons and her colleagues believe this unidentified lead source is potentially derived from the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway but requires further investigation. Fitzsimmons would also like to see better transport modeling of sediments conducted in Galveston Bay in future studies.

“In this study, I wanted to apply my analytical toolbox to a more local area with greater human impact,” Fitzsimmons says. “The best news is that our results showed that lead concentrations in sediments in “our backyard waters” fall below toxicity thresholds.”

This research was funded by the Galveston Bay Estuary Program and the Texas A&M T3 Triad Program.

By Justin Agan ‘18