Extraordinary Ocean Floor Cores Speak To Ancient Climate Shifts, Texas A&M Dean Says

Dr. Debbie Thomas, Dean of the College of Geosciences at Texas A&M, spent five weeks co-leading International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 378, which recovered the sediment cores in the South Pacific.

Feb 28, 2020

Expedition 378 Co-Chief Scientists Dr. Ursula Röhl and Dr. Debbie Thomas. (Photo credit: Tim Fulton, IODP JRSO.)

With the very first core of the expedition, Daniel Marone, IODP JRSO Electronics Specialist, Nicolette Lawler, IODP JRSO Marine Laboratory Specialist, and others. (Photo credit: Yiming Yu and IODP.)

Nearly 1,000 meters of sediment cores from the deep ocean floor were recently recovered by International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 378 in the eastern South Pacific Ocean. Paleoclimate scientists around the world are especially excited about the time interval that these cores span, says the Texas A&M scientist who co-led the expedition.

“We recovered three sets of cores of the time period spanning about 25 to 36 million years ago, and what’s important about this interval of time is that it captures the early phases of interglacial variability on Antarctica, but during a climate state that’s actually warmer than our current climate state,” said Dr. Debbie Thomas, dean of the College of Geosciences at Texas A&M University, paleoceanographer and co-chief scientist of the expedition.

“Included in those three sets of cores is the prominent climate event that occurred 34 million years ago known as the Eocene-Oligocene transition, which marks the first major build-up of ice on Antarctica as the planet cooled from the extreme warmth,” she said. “Many of our expeditions’ scientists, as well as the broader paleoclimate community, are really interested in understanding that event.”

The expedition successfully recovering this time-segment three times (in three separate holes at the same location) is critically important, because it gives scientists more material to work with, but also a more complete overall record through time, she said.

“Not only that, but in two deeper holes we drilled, we recovered two complete copies of the rapid global warming event at 56 million years ago, which was another one of the primary objectives of the entire expedition”

Expedition 378: South Pacific Paleogene Climate

Sailing aboard the JOIDES Resolution (JR) research vessel, Expedition 378 began Jan. 3 out of Lautoka, Fiji, and concluded Feb. 6 in Papeete, Tahiti.

Co-chief Scientists Thomas and Dr. Ursula Röhl, from the MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen in Germany, led the 35-person science party in investigating the record of Cenozoic climate and oceanography in the southern Pacific Ocean, by recovering and studying deep ocean sediment cores.

“Expedition 378 set out to recover the sediment sequences from a location south of New Zealand, IODP Site U1553, which is critical to scientists’ understanding of high-latitude environmental conditions, ocean circulation, and wind patterns during a time in recent earth history characterized by the evolution of climate from extreme warmth into a climate state that supported the growth of ice sheets on Antarctica,” Thomas said.

IODP and Texas A&M have a long history: since 1985 Texas A&M has served as the host of JOIDES Resolution science operations, and the JOIDES Resolution Science Operator (JRSO) is based in the Texas A&M College of Geosciences. Two of the three IODP ocean sediment core repositories are housed at Texas A&M and at the MARUM at the University of Bremen. IODP is funded by the National Science Foundation and other participating countries.

Conducting Critically Needed Science, Even With A Shortened Itinerary

About 10 days before the expedition began, Thomas and Röhl learned from IODP and JRSO leadership that an inspection of the JOIDES Resolution’s derrick revealed that it could not drill in waters deeper than 2 kilometers, eliminating four of the five drill sites originally planned for Expedition 378, and therefore shortening the overall expedition.

“Science conducted at sea is an inherently risky operation, and successful data collection truly relies on an alignment of stars — favorable weather and sea state, properly functioning sampling equipment, and a safely functioning research vessel,” Thomas wrote at the time. “Safety is paramount. All sea-going scientists have their tale of misaligned stars.”

Thomas and Röhl regrouped and worked with JRSO Director Dr. Brad Clement to quickly adjust the expedition’s plans for only drilling at one site instead of five: Site U1553, located south of New Zealand.

“The only way forward was positive,” Thomas said. “Everyone onboard the ship is giving up time, everyone is enduring some sacrifice — so it really fell on us to make sure that, not only was the experience as positive and formative as possible, but that everyone came away with really impactful science.”

Decades before this voyage, cores from the same location as Site U1553 had been recovered by IODP’s predecessor, the Deep See Drilling Project (DSDP), aboard the Glomar Challenger drillship, in 1973. But the modern, state-of-the art drilling and laboratory equipment on the JOIDES Resolution and IODP’s scientific advances in drilling and analyzing sediments made a revisit to the site a very strategic endeavor.

“In 2020 we return to DSDP site 277. We give it a new name, a couple new holes, and the best scientific analysis we can muster,” wrote Expedition 378 outreach officer Lindy Newman during the voyage. “In 2020 we call it IODP Site U1553, because even after all our scientific advancements, the Earth still has secrets to reveal.”

How To Lead A Floating, Never-stopping, Multilingual Science Station

What is it like to co-lead a science team of experts from all over the world — sedimentologists, micropaleontologists, petrologists, chemists, paleomagnetists, downhole logging specialists, and equipment technicians — all constantly working in 12-hour shifts, on a tight schedule, in the middle of the ocean, while also coordinating with a crew of professional drill operators?

“Serving as co-chief was a stressful blast,” Thomas said.

Even before sailing, the science that they proposed for the expedition “required a tremendous amount of planning,” she said. “Then we worked with the program management offices in our various IODP member consortia and nations to select the ideal group of scientists to help us achieve these scientific objectives.”

Aboard the JOIDES Resolution, a co-chief scientist’s day is very busy. Thomas led the day shift, which was noon to midnight, and Röhl led the night shift, from midnight to noon.

“Once we reach the drill site, the co-chief’s job is to really help guide decision making about drilling,” she explained. “It’s working with the drillers and the operations team to best use the time that we have available for drilling operations. And so in our case, we had to balance getting redundant but critical replication of different portions of the sediment sequence in the five separate holes drilled at Site U1553.”

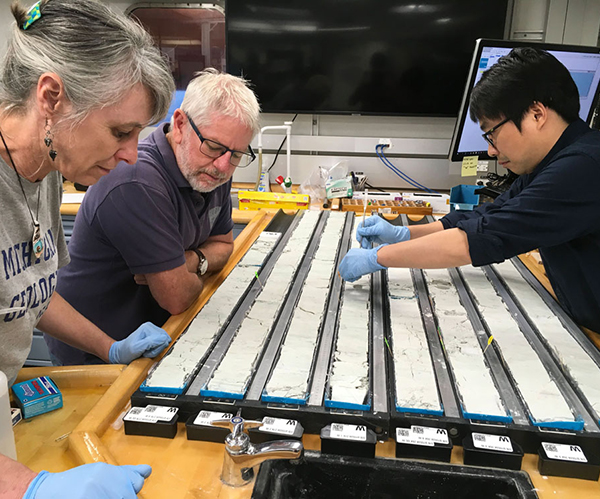

At the sampling table: Ingrid Hendy, sedimentologist, University of Michigan; Christopher Hollis, observer/micropaleontologist, GNS Science, New Zealand; and Wei Yuan, paleomagnetist, Tongji University, China. (Photo credit: Lindy Newman and IODP.)

Siem Offshore personnel place the drill bit into position on the rig floor. (Photo credit: Tim Fulton, IODP JRSO.)

Natural gas levels in the sea floor, equipment issues, goals to replicate multiple copies of cores or fill in gaps identified in the previous holes, as well as weather conditions, are all factors that the co-chiefs and the operators consider in making their drilling decisions.

“We had to make constant decisions, working with our stratigraphic correlator, the drillers, the operations manager — every time a core came up, we examined the how much core was recovered relative to how far the driller advanced the hole depth and had to decide for the next core if we attempt a full, 10m advance, or a half advance, or was this the time when we should switch from the piston corer to the extended core barrel?”

A Diverse Team, Immersed In Science, 24/7

Scientists aboard the JOIDES Resolution are required to work in 12-hour shifts, 7 days a week. For relaxation and recreation, they enjoy a “phenomenal gym, a great movie room, musical instruments and games,” Thomas said.

“But, part of the recreation is in the luxury of being able to immerse ourselves in science, without having to do laundry or cook or any of those usual things. It really is a rare gift to be able to recapture why you were passionate about this science in the first place, and to get to engage in interdisciplinary problem-solving for huge chunks of the day.”

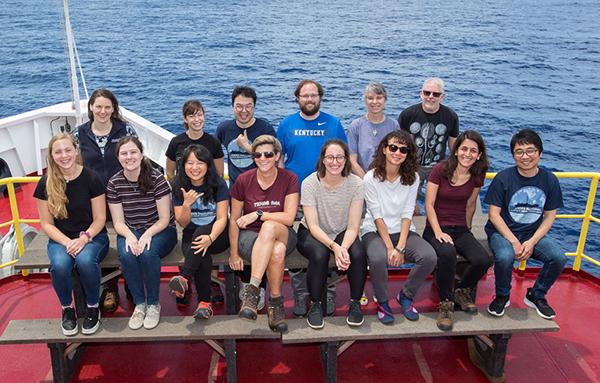

Another noteworthy aspect of Expedition 378’s science team was that it was uniquely diverse.

“We were the first science party to sail on the JOIDES Resolution in which the three primary leadership roles as well as the lab officer all were filled by women, and the majority of the entire science party was female — absolutely amazing,” she explained. “I think that the diverse composition of the science party is a really important triumph to share with children, and students in college and graduate school, who are thinking about a career in science.”

After this extraordinary team processed the last core, packed up the drill pipe, raised the thrusters, and waved goodbye to site U1553, the science party still had years of progress and discoveries to look forward to.

“We’ve laid a foundation for these scientists to do some amazing science over the next four years and beyond,” Thomas said. “And I think we’ve also shown the early career team members that a career in science is not only going to be rewarding, but it’s going to be fun, and they’ll have a chance to feel supported in the community that we’ve created with this shipboard science party.”

In April, the sediment cores from Expedition 378 will arrive at the IODP Gulf Coast Repository, housed at Texas A&M, for sampling and x-ray florescence analysis, and the science party will gather for its post-cruise meeting.

“This is just an immensely talented group of scientists. The quality of the science is going to be unbelievable.”

By Leslie Lee ’09