Texas A&M And FSU Researchers Find Depleted Seamounts Near Hawaii Recovering After Decades Of Federal Protection

Dr. Brendan Roark co-authored game-changing research on the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain.

Aug 13, 2019

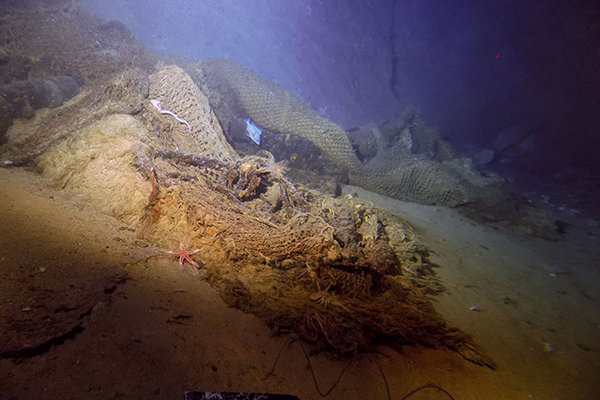

Lost trawl net from on the NW Hancock Seamount at a depth of 400m. (Photo by A. Baco-Taylor FSU, E.B. Roark TAMU, NSF, with HURL Pilots T. Kerby and M. Cremer)

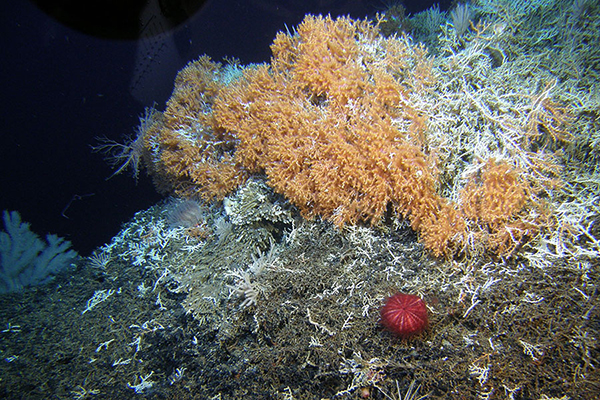

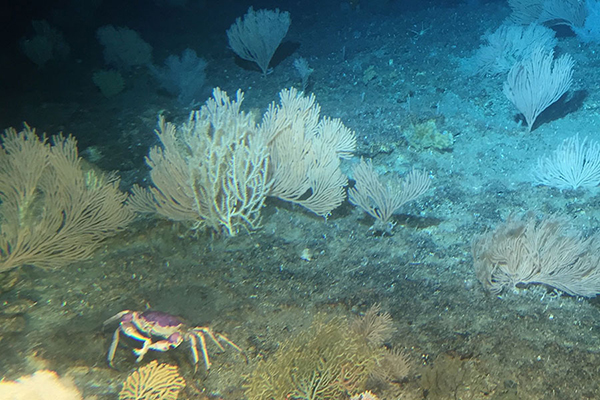

For decades, overfishing and trawling devastated parts of an underwater mountain range in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii, wrecking deep-sea corals and destroying much of their ecological community.

But now, after years of federally mandated protection, scientists see signs that this once ecologically fertile area known as the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain is making a comeback.

The research team who discovered the evidence of recovery was led by Dr. Brendan Roark, associate professor in the Department of Geography at Texas A&M University, Dr. Amy Baco-Taylor, Florida State University (FSU) associate professor of oceanography, and FSU doctoral student Nicole Morgan. The research was funded by NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences and involved four research cruises out to the central and north Pacific Ocean to investigate the ecological communities of the region.

Because of the slow-growing nature of the corals and sponges that live on seamounts, “It’s been hypothesized that these areas, if they’ve been trawled, that there’s not much hope for them,” Baco-Taylor said.

“So, we explored these sites fully expecting to not find any sign of recovery,” she said. “But we were surprised to find evidence that some species are starting to come back to these areas.”

The researchers published their findings this week in Science Advances. The overall understanding that a trawled seamount could recover is a game-changer in terms of fishing management.

“This is a high-impact paper that bears directly on fishery management issues in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands and is timely relative to some changes the current administration is thinking about with respect to opening up marine monuments for more fishing,” Roark said.

Scientists and policymakers regularly debate whether protected areas could be reopened for fishing.

“This is a good story of how long-term protection allows for recovery of vulnerable species,” Baco-Taylor said.

The Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain is a mostly underwater mountain range in the Pacific Ocean. From the 1960s through the 1980s, the area was a hotbed for fishing and a practice called trawling, where fishermen use heavy nets dragged along the seafloor to capture fish. In the process, the nets scrape other animals off the seafloor as well.

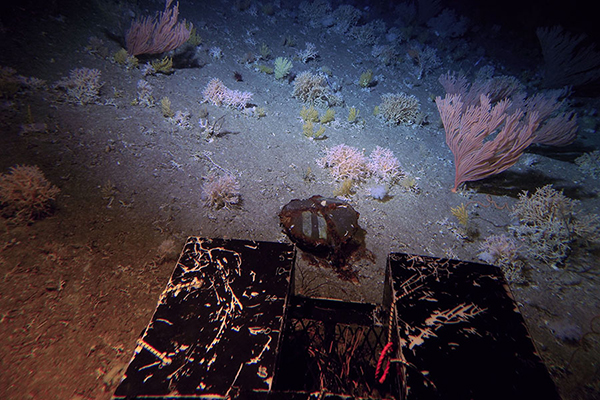

The practice of trawling has devastated seamounts around the world and scientists have generally believed that an ecological recovery was unlikely. However, in the case of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain, there is a glimmer of hope.

They specifically wanted to examine whether there was any recovery of life on the seamount chain, because unlike other submerged mountain chains around the world, this one had been federally protected from fishing and trawling for decades.

In 1977, the United States claimed the region as a part of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which prevented foreign fleets from trawling the area. In 2006, then President George W. Bush included the area as part of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, further protecting it from human disturbance.

“People started realizing how vulnerable seamounts were relatively recently, so seamounts in other locations have only been protected for 5 to 15 years,” Baco-Taylor said. “Establishment of the U.S. EEZ in this region, has provided protection for these sites for close to 40 years, providing a unique opportunity to look at recovery on longer time scales.”

The team analyzed 536,000 images. In them, they could not only see the remnant trawl scars on the seafloor, they also saw baby coral springing up in those areas. They could also see coral regrowing from fragments on fishing nets that were left on the seafloor.

“We know the stuff growing on the net had to come after this practice stopped in the area,” Morgan said.

Most importantly, they found evidence of a few precious areas that were not harmed by the trawling. These untouched areas are crucial to further populating the seamounts with a variety of fauna, researchers said.

It’s too early to say how long it took for the new coral to arrive and whether the area will return to its former glory. Scientists are still analyzing coral samples to determine the age and diversity of species in the area.

Roark said this study and the ongoing work provides critical knowledge for policymakers examining the effectiveness of protecting these areas.

Written in collaboration with Kathleen Haughney, Florida State University.